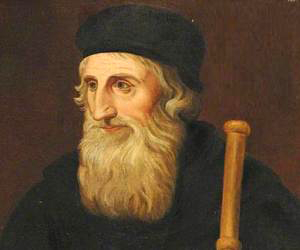

John Wycliffe circa 1328 - 1384

He strongly believed that everyone should be able to benefit from God's Word. But in his time, the common people in England had virtually no access to the Bible. Wycliffe believed that each man was directly accountable to God. But if each person was directly accountable to God, then they needed to have the Bible translated into their own language. You can catch Wycliffe's passion and directness in these words of his:

"Those Heretics who pretend that the laity need not know God's law but that the knowledge which priests have had imparted to them by word of mouth is sufficient, do not deserve to be listened to. For Holy Scriptures is the faith of the Church, and the more widely its true meaning becomes known the better it will be. Therefore since the laity should know the faith, it should be taught in whatever language is most easily comprehended… [After all,] Christ and His apostles taught the people in the language best known to them".

John Wycliffe, Speculum Secularium Dominorum, Opera Minora

In 1382, the English translation later known as the Wycliffe Bible was produced. Just how much John Wycliffe actually translated is himself is unknown today, contributors were, John Purvey, John Trevesa, Nicholas Hereford. What was the reaction of the clergy? They showed hatred for Wycliffe, his Bible, and his followers. The religious authorities persecuted the Lollards and hunted down and destroyed as many copies of the Wycliffe Bible as they could find. In 1378, the year of the "Great Schism of the West" involving the papacy, John Wycliffe published his translation of the New Testament (the Christian Greek Scriptures). "Wycliffe translated directly from the Latin Vulgate, not deeming himself competent to use the Hebrew and Greek originals as a basis. So back in the 14th century Wycliffe was using the word "minister." No doubt William Tyndale "largely used it in his translation from the original tongues." At Romans 13:4 Wycliffe's translation reads: "He is the mynystre of God." At Romans 11:13: "I schal onoure my mynysterie." What is the significance of the Wycliffe translation? It was the first complete Bible in English—in fact, the first complete Bible in any modern European language! It indirectly began to break down the power structures of the political-religious machinery of the Roman Catholic church. Lay folks did not need to rely on the priests to access God. And they could know his will and even challenge their spiritual leaders. It is no wonder that by 1408 even reading the Bible in English was outlawed. People owned a copy at risk of liberty and life. So powerful was Wycliffe's influence in fact that in 1415 the Pope decreed that his bones should be dug up, burned, and the ashes scattered on the River Swift. The translation was completed more than sixty years before the invention of the movable-type printing press. All Wycliffe Bibles were thus handwritten copies. This lessened its impact considerably. And even though one Bible could take up to a year to copy, thousands were made. 256 survive in whole or in part.

Main Beliefs of Wycliffe

- The Bible is the source of all truth and should be available in the language of the common people.

- Christs presence in the bread and the wine is purely figurative

- The veneration of images is unscriptual and therefore unacceptaple

- Every lay person is a priest

- The practice of pilgrimage and the sale of indugences are valueless in God's sight.

- The Pope and the church execise excessive authority

Queen Anne 1389-1409 (died 19yrs old)

Jan Hus 1372-1415

Strongly influenced by John Wycliffe was the Bohemian (Czech) Jan Hus, also a Catholic priest and rector of the University of Prague. Anne, the queen of England and wife of Richard II, had a Latin Bible and one in her own Bohemian language. The marriage in 1382 had been agreed to by her brother King Wenceslaus, on the advice of the Pope, who wished to serve his own ends but did not anticipate the result. Members of the Prague Court visiting her took some of Wycliffe's works back to Bohemia. Prague University also forged links with Oxford University. As a result of this contact, John Huss came to read the writings of John Wycliffe. Like Wycliffe, Hus preached against the corruption of the Roman Church and stressed the importance of reading the Bible. This quickly brought the wrath of the hierarchy upon him. In 1403 the authorities ordered him to stop preaching the antipapal ideas of Wycliffe, whose books they also publicly burned. Hus, however, went on to write some of the most stinging indictments against the practices of the church, including the sale of indulgences. He was condemned and excommunicated in 1410. Hus was uncompromising in his support for the Bible. "To rebel against an erring pope is to obey Christ," he wrote. He also taught that the true church, far from being the pope and the Roman establishment, "is the number of all the elect …., whose head Christ is; and the bride of Christ, whom of his great love he redeemed with his own blood." (Compare Ephesians 1:22, 23; 5:25-27.) For all of this, he was tried at the Council of Constance and was condemned as a heretic. Declaring that "it is better to die well than to live ill," he refused to recant and was burned to death at the stake in 1415. The same year Wycliffe's writings were banned and Wycliffe was declared a heretic. The same council also ordered that the bones of Wycliffe be dug up and burned even though he had been dead and buried for over 30 years!

Wessel Gansfort 1419 -1489

In 1473, Wessel visited Rome. There he had an audience with Pope Sixtus IV, the first of six popes whose grossly immoral conduct largely contributed to the Protestant Reformation. The Pope asked him what he would like Wessel answered: "Then I ask that you give me a Greek and Hebrew Bible from the Vatican Library." The Pope granted his request but remarked that Wessel had acted foolishly and that he should have asked for a bishopric! His love for the original languages of the Bible is particularly remarkable, since he lived before Erasmus and Reuchlin. Before the Reformation, knowledge of Greek was rare. In Germany, only a handful of scholars were familiar with Greek, and there were no tools available to learn the language. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Wessel apparently came in contact with Greek monks who had fled to the West, and he learned from them the rudiments of Greek. In those days, Hebrew was restricted to the Jews, and it seems that Wessel learned basic Hebrew from converted Jews. According to the book A History of Christianity, Wessel "held that, being inspired by the Holy Spirit, the Bible is the final authority in matters of faith."

WESSEL AND GOD'S NAME

In Wessel's writings, the name of God is generally rendered "Johavah." However, Wessel used "Jehovah" on at least two occasions. In discussing the views of Wessel, author H. A. Oberman concludes that Wessel felt that if Thomas Aquinas and others had known Hebrew, "they would have discovered that the name of God revealed to Moses does not mean 'I am who I am,' but 'I will be who I will be.'" The New World Translation correctly gives the meaning "I shall prove to be what I shall prove to be."—Exodus 3:13, 14.

Some his works are said to have been burned by his friends shortly after his death for fear of ecclesiastical inquisition.

Andreas Karlstadt 1486 -1541

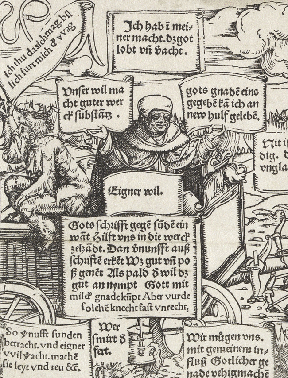

Karlstadt's Cartoon by Lucas Cranach 1519

This remarkable cartoon, produced by artist Lucas Cranach and the Wittenberg theology professor Andreas Karlstadt, is almost certainly the very first piece of visual propaganda for the Reformation. Karlstadt was finalizing the Latin version of his broadsheet in January 1519; the first printed image of Luther, a crude woodcutadorning a tract printed in Leipzig, did not appear until at least six months later. The Reformation of course owed much of its success to its ability to exploit the new media of woodcut and print; and the partnership between the theologian Martin Luther and the Lucas Cranach, who lived just around the corner, was crucial to the Reformation's success. Cranach's famous portraits of Luther shaped his image throughout the entire sixteenth century. He collaborated with Philipp Melanchthon and Johann Schwertfeger, to produce the Passion of Christ and Antichrist in 1521, one of the most influential pieces of propaganda for the Reformation. Cranach's workshop produced the woodcuts for Luther's Bible, and as late as 1545, the two worked together to produce a series of scurrilous cartoons against the Roman Papacy to accompany the work of Luther. But as this cartoon demonstrates, it was Karlstadt, not Luther, who first conceived the idea of working with Cranach in the service of the new religious ideas, and who forged the partnership between artist and theologian.

Cranach’s woodcut of wagons, horses and men travelling to Heaven and to Hell was executed with vigour and skill. Around the beginning of 1519 Karlstadt began to spread the new Wittenberg theology of grace through pamphlets written in German. The broadsheets set off heated debate in print. In the summer of 1520 Eck included Karlstadt in the Roman bull threatening excommunication. In response, Karlstadt published a pamphlet in October 1520 which he demonstrated "by means of Holy Scripture ... that the holy pope can err, sin, and commit injustices"

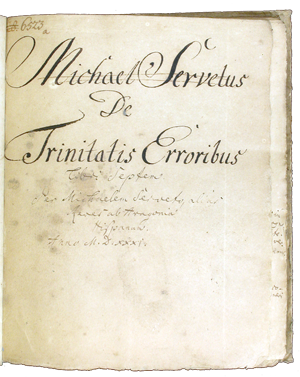

Michael Servetus 1511 - 1553

In the year 1528 an Italian monk named Sanctes Pagninus published in Lyons, France, a work on which he had labored for thirty years. Its Latin title, translated into English, is "A New Translation of the Old and the New Testament." Later an edition of this was published in Lyons, in 1542, by Servetus.

On October 27, 1553, Michael Servetus was burnt alive in 1553 by Protestants led by John Calvin in the Champel district of Geneva for having denied the Trinity. Servetus' quest for the truth also led him to use the name Jehovah. Some months after William Tyndale employed this name in his translation of the Pentateuch, Servetus published On the Errors of the Trinity—in which he used the name Jehovah throughout. In his final work, The Restitution of Christianity, Servetus stated regarding the divine name, Jehovah: "[It] is clear . . . that there were many who pronounced this name in ancient times." Guillaume Farel—the executioner and vicar of John Calvin—warned the onlookers: "[Servetus] is a wise man who doubtless thought he was teaching the truth, but he fell into the hands of the Devil. . . . Be careful the same thing does not happen to you!" What had this unfortunate victim done to deserve such a tragic fate? MICHAEL SERVETUS was born in 1511 in the village of Villanueva de Sijena, Spain. From an early age, he excelled as a student. According to one biographer, "by the time he was 14 years of age, he had learned Greek, Latin, and Hebrew, and he had an ample knowledge of philosophy, mathematics, and theology." When Servetus was still a teenager, Juan de Quintana, the personal confessor of Spanish Emperor Charles V, employed him as a page. In his official journeys, Servetus could observe the underlying religious divisions in Spain, where Jews and Muslims had been exiled or forcibly converted to Catholicism. Spanish authorities banished 120,000 Jews who refused to accept Catholicism, and several thousand Moors were burned at the stake. At the age of 16, Servetus went to study law at the University of Toulouse, in France. There he saw a complete Bible for the first time. Although reading the Bible was strictly forbidden, Servetus did so in secret. After completing his first reading, he vowed to read it "a thousand times more." Probably, the Bible that Servetus studied in Toulouse was the Complutensian Polyglot, a version that enabled him to read the Scriptures in the original languages (Hebrew and Greek), along with the Latin translation. His study of the Bible, together with the moral degeneracy of the clergy that he had seen in Spain, shook his faith in the Catholic religion. Servetus' doubts were reinforced when he attended the coronation of Charles V. The Spanish king was crowned emperor of the Holy Roman Empire by Pope Clement VII. The pope, seated on his portable throne, received the king, who kissed his feet. Servetus later wrote: "I have seen with my own eyes how the pope was carried on the shoulders of the princes, with all the pomp, being adored in the streets by the surrounding people." Servetus found himself unable to reconcile that pomp and extravagance with the simplicity of the Gospel.

His Quest for Religious Truth

Servetus discreetly left his employment with Quintana and began his solitary search for the truth. He believed that Christ's message was not directed to theologians or philosophers but to common people who would grasp it and put it into practice. Thus, he resolved to consult the Bible text in the original languages and to reject any teaching at odds with the Scriptures. Interestingly, the word "truth" and its derivatives appear more often than any other word in his writings.

Servetus' historical and Biblical studies led him to the conclusion that Christianity had become corrupted during the first three centuries of our Common Era. He learned that Constantine and his successors had promoted false teachings that eventually led to the adoption of the Trinity as an official doctrine. At the age of 20, Servetus published his book On the Errors of the Trinity, a work that made him a principal target of the Inquisition. Servetus saw things clearly. "In the Bible," he wrote, "there is no mention of the Trinity. . . . We get to know God, not through our proud philosophical concepts, but through Christ." He also came to the conclusion that the holy spirit is not a person but, rather, God's force in action. Servetus did provoke some favourable response. Protestant Reformer Sebastian Franck wrote: "The Spaniard, Servetus, contends in his tract that there is but one person in God. The Roman church holds that there are three persons in one essence. I agree rather with the Spaniard." Nevertheless, neither the Roman Catholic Church nor the Protestant churches ever forgave Servetus for challenging their central doctrine. The study of the Bible also led Servetus to reject other church doctrines, and he considered the use of images to be unscriptural. Thus, a year and a half after publishing On the Errors of the Trinity, Servetus said with respect to both Catholics and Protestants: "I do not agree or disagree in everything with either one party or the other. Because all seem to me to have some truth and some error, but everyone recognizes the other's error and nobody discerns his own." His was a solitary quest for the truth. His sincerity, however, did not prevent Servetus from reaching some mistaken conclusions. For example, he calculated that Armageddon and the Millennial Reign of Christ would come during his own lifetime.

A Formidable Opponent

Seekers of the truth have always had many opponents. (Luke 21:15) Among Servetus' many adversaries was John Calvin, who had established an authoritarian Protestant state in Geneva. According to historian Will Durant, Calvin's "dictatorship was one not of law or force but of will and character," and Calvin "was as thorough as any pope in rejecting individualism of belief." Servetus and Calvin probably met in Paris when they were both young men. From the outset their personalities clashed, and Calvin became Servetus' most implacable enemy. Although Calvin was a leader of the Reformation, he finally denounced Servetus to the Catholic Inquisition. Servetus barely succeeded in escaping from France, where he was burned in effigy. However, he was recognized and imprisoned in the frontier city of Geneva, where Calvin's word was law. Calvin meted out cruel treatment to Servetus in prison. Nevertheless, in his debate with Calvin during the trial, Servetus offered to modify his views, provided his opponent gave Scriptural arguments to convince him. Calvin proved unable to do so. After the trial, Servetus was condemned to be burned at the stake. Some historians claim that Servetus was the only religious dissenter who was both burned in effigy by the Catholics and burned alive by the Protestants.

A Herald of Religious Freedom

Although Calvin eliminated his personal rival, he lost his own moral authority. The unjustified execution of Servetus outraged thinking people throughout Europe, and it provided a powerful argument for civil libertarians who insisted that no man should be killed for his religious beliefs. They became more determined than ever to press on in the fight for religious freedom.

Italian poet Camillo Renato protested: "Neither God nor his spirit have counselled such an action. Christ did not treat those who negated him that way." And French humanist Sébastien Chateillon wrote: "To kill a man is not to protect a doctrine, but it is to kill a man." Servetus himself had said: "I consider it a serious matter to kill men because they are in error on some question of scriptural interpretation, when we know that even the elect ones may be led astray into error." Regarding the lasting impact of Servetus' execution, the book Michael Servetus—Intellectual Giant, Humanist, and Martyr says: "Servetus's death was the turning point in the ideology and mentality dominating since the fourth century." It adds: "From a historical perspective, Servetus died in order that freedom of conscience could become a civil right of the individual in modern society."

In his work A Statement Regarding Jesus Christ, Servetus described the doctrine of the Trinity as perplexing and confusing and noted that the Scriptures contained "not even one syllable" in its support. While in prison, Servetus signed his last letter with these words: "Michael Servetus, alone, but trusting in Christ's most sure protection."

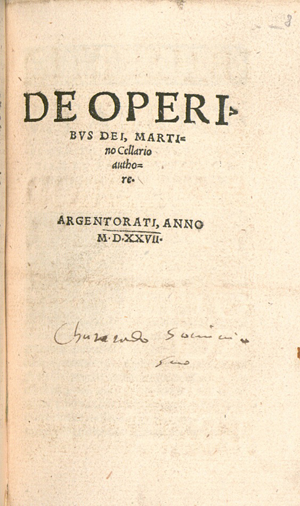

Title page from De Operibus Dei (On the Works of God) Title page of Martin Cellarius' book On the Works of God, in which he compared church teachings with the Bible

On October 27, 1553, Michael Servetus was burned at the stake in Geneva, Switzerland. Guillaume Farelthe executioner and vicar of John Calvin, warned the onlookers: "[Servetus] is a wise man who doubtless thought he was teaching the truth, but he fell into the hands of the Devil. . . . Be careful the same thing does not happen to you!" What had this unfortunate victim done to deserve such a tragic fate? Probably, the Bible that Servetus studied in Toulouse was the Complutensian Polyglot, a version that enabled him to read the Scriptures in the original languages (Hebrew and Greek), along with the Latin translation. In 1542, Servetus also edited the renowned Latin translation of the Bible by Santes Pagninus, In his extensive marginal notes, Servetus highlighted the divine name again. He included the name Jehovah in the marginal references to key texts such as Psalm 83:18, where the word for "Lord" appeared in the main text.) Thus, a year and a half after publishing On the Errors of the Trinity, In his final work, The Restitution of Christianity, Servetus stated regarding the divine name, Jehovah: "[It] is clear . . . that there were many who pronounced this name in ancient times.") His study of the Bible, together with the moral degeneracy of the clergy that he had seen in Spain, shook his faith in the Catholic religion. Forced to flee from his persecutors, Servetus changed his name to Villanovanus and settled in Paris, where he obtained degrees in art and medicine. Servetus and Calvin probably met in Paris when they were both young men. From the outset their personalities clashed, and Calvin became Servetus' most implacable enemy. Although Calvin was a leader of the Reformation, he finally denounced Servetus to the Catholic Inquisition. Servetus barely succeeded in escaping from France, where he was burned in effigy. However, he was recognized and imprisoned in the frontier city of Geneva, where Calvin's word was law. After the trial, Servetus was condemned to be burned at the stake. Some historians claim that Servetus was the only religious dissenter who was both burned in effigy by the Catholics and burned alive by the Protestants.

Girolamo Savonarola 1452-1498